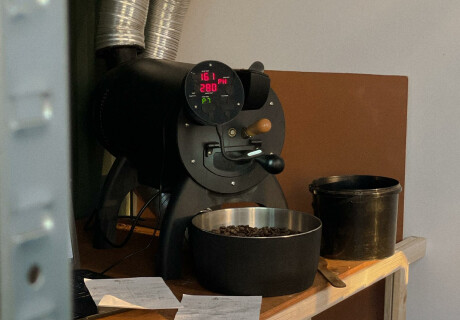

Inside the BEAN - What happens during coffee roasting?

Coffee roasting transforms humble green beans into the aromatic brown beans we know and love. This complex process involves numerous chemical reactions and physical changes that develop the rich flavors we enjoy in our daily cup. In this comprehensive guide, we'll explore the fascinating science behind coffee roasting, from the molecular transformations to practical roasting techniques that bring out the best in every bean.

The Composition of Green Coffee Beans

Before diving into the roasting process, it's important to understand what we're starting with. Unroasted green coffee beans contain:

- Polysaccharides (cellulose, pectins)

- Water (approximately 8-12% of bean mass)

- Proteins (various amino acids)

- Lipids (coffee oils)

- Organic acids (chlorogenic acids, citric acid, malic acid)

- Caffeine

In their raw state, green beans are hard with a grayish-green color and a subtle, grassy aroma. Most of the compounds responsible for coffee's distinctive flavor haven't formed yet. Instead, the beans contain precursors like sugars and amino acids needed for the Maillard reaction, sucrose for caramelization, and chlorogenic acids that influence acidity. Caffeine is already present and remains relatively stable throughout the roasting process.

Chemical Reactions During Coffee Roasting

When exposed to increasing temperatures, coffee beans undergo various chemical reactions that build the rich flavor and aroma profile of roasted coffee. Let's explore the most important ones:

The Maillard Reaction: Foundation of Coffee Flavor

The Maillard reaction is the crucial process that shapes the flavor of roasted coffee. It occurs when amino acids (from bean proteins) react with reducing sugars under high temperatures. This reaction begins around 140-150°C (284-302°F) and results in hundreds of aromatic-flavor compounds and dark pigments called melanoidins.

These melanoidins give the beans their brown color and contribute to flavor notes described as roasted, nutty, bready, or cocoa-like. The Maillard reaction releases nutty, roasted, malty, and even floral and fruity notes, adding tremendous complexity to coffee's flavor profile.

During the Maillard transformations, a process called Strecker degradation also occurs. This process transforms amino acids into aldehydes (volatile aromatic compounds) while releasing carbon dioxide (CO₂) and ammonia. The resulting Strecker aldehydes strongly influence the aroma of freshly roasted coffee—for example, phenylacetaldehyde creates a floral-honey scent, while 3-methylbutanal (from valine/leucine) contributes a malty or grain-like aroma.

Caramelization of Sugars: Source of Sweetness and Bitterness

Another important reaction is caramelization—the thermal breakdown of simple sugars and sucrose that occurs intensively above 170-180°C (338-356°F). Unlike the Maillard reaction, caramelization doesn't require amino acids. Instead, sugars gradually melt and break down, creating new compounds with sweet, caramel, toffee, or chocolate-like notes.

At a certain stage, caramelization products also darken, contributing to the brown color of roasted beans. Moderate caramelization adds pleasant sweetness and notes reminiscent of caramel or roasted almonds. However, excessive caramelization results in sugars breaking down into bitter compounds—which is why very dark roasted coffee may taste burnt and distinctly bitter.

Controlling the roasting profile (time and temperature) is critical to balance the Maillard reaction and caramelization, extracting sweetness and rich flavor while avoiding burning the beans.

Breakdown of Proteins and Other Complex Compounds

High temperatures also cause denaturation and breakdown of proteins present in coffee beans. Proteins break down into free amino acids, which—as described above—enter Maillard and Strecker reactions, creating important aroma precursors.

Protein breakdown can also release sulfur-containing amino acids (like cysteine and methionine), which contribute to the formation of sulfur compounds with very intense aromas. For example, 2-furfurylthiol, one of the key aromas in freshly roasted coffee, creates the characteristic "coffee" smell (reminiscent of roasted malt and rum) and forms partly through sulfur compounds during roasting.

Simultaneously, chlorogenic acids—the most abundant organic acids in green coffee—undergo degradation (hydrolysis) into caffeic and quinic acids, which influence the taste of the brew. Caffeic acid adds bitterness and astringency, while quinic acid (also a component of green beans) affects perceived acidity.

The lighter the roast, the more chlorogenic acids preserved—which is why light roasts have higher acidity and sharper taste, while dark roasts break down most of these acids, resulting in a smoother, less acidic brew.

Formation of Aromatic Compounds

The result of these reactions is a rich cocktail of volatile compounds that determine the aroma of roasted coffee. Scientists estimate that freshly roasted coffee contains over 800-900 different volatile compounds, with several dozen having a key impact on perceived smell.

These include:

- Aldehydes (providing floral, fruity, or "green" notes)

- Ketones

- Furans (caramel, malty aromas)

- Pyrazines (nutty-roasted notes)

- Sulfur compounds (adding intense "roasted" scent)

- Phenols like guaiacol (smoky, spicy smell)

For example, Arabica's aroma is dominated by furan and pyrazine derivatives responsible for its characteristic "bakery" and nutty bouquet. Volatile compounds are partially retained within the bean's structure and by the oils covering the bean, preserving the aroma until grinding and brewing. That's why freshly ground coffee smells so intense—grinding releases these aromas stored inside the bean.

Gas Release and First/Second Crack

During roasting, gases are intensively emitted from within the beans. The most important is carbon dioxide (CO₂), which forms as a byproduct of many thermal reactions—including the Maillard reaction, Strecker degradation, and the breakdown of organic acids and plant fibers.

These gases accumulate inside the bean cells, causing internal pressure to increase. At a certain point, this pressure finds a way out—the bean structure can't withstand it, and there's a sudden release of water vapor and gases, accompanied by an audible crack. This is the "first crack"—a key moment signaling the bean's transition to the proper roasting phase.

The first crack typically begins at around 196°C (385°F) inside the bean and indicates that the bean has reached a light/medium degree of roasting. The reason for this "popcorn-like" crack is mainly the explosive evaporation of accumulated water and steam escaping from inside the bean, rupturing its structure.

If roasting continues, a "second crack" may occur after some time, usually when the beans reach a very dark roasting degree (around 220-230°C/428-446°F). The second crack has a different character—the cracks are quieter, more like sizzling. This time, accumulated CO₂ and further disruption of the cellular structure play the main role. At this stage, the cells are already dried and brittle, so they crack more easily, and coffee oils emerge to the surface.

The second crack signals French or Italian roast (very dark), where smoky, heavily roasted notes appear, and acidity is practically completely suppressed.

Physical Changes in Coffee Beans During Roasting

Alongside chemical reactions, dramatic physical changes occur in the coffee beans themselves. Water loss and gas accumulation transform the structure—beans swell, crack, and become porous. Here are the most important physical effects of roasting:

Loss of Mass and Moisture

In the initial phase of roasting (the drying phase, up to about 150°C/302°F), the bean loses most of its water. Moisture content drops from ~10-12% to just 1-3% after roasting is complete. Some volatile compounds escape with the water vapor as well. Overall, the bean loses about 15-18% of its initial mass during roasting—primarily due to water loss but partly also due to the loss of volatile substances.

For example, 1 kg of green beans might yield about 850 g of roasted coffee. This mass loss is sometimes called the "roasting index" and is monitored by roasters to assess the degree of roasting (the darker the roast, the higher the loss).

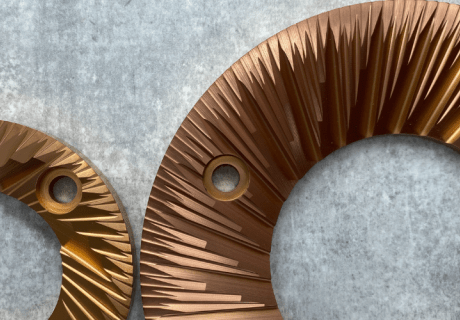

Volume Increase and Cell Rupture

As water turns to steam and gases collect inside the bean, its volume begins to increase. Just before the first crack, the bean swells rapidly, and at the moment of cell explosion, it dramatically increases in volume. Overall, beans double their volume (an increase of 50-100%) compared to their raw state.

The bean's surface cracks at its weakest points (most often along the center groove). The silver skin covering the bean also detaches—visible as chaff in the form of dry, light fragments floating in the roaster. After the first crack, the bean structure becomes brittle and porous.

Further heating (toward the second crack) causes more cracks and micro-fissures in the cell walls, increasing porosity. Microscopic studies show that between green and medium-roasted beans, there's a dramatic increase in internal porosity—cells form numerous empty spaces, and cell walls are partially destroyed. In dark-roasted beans, porosity is already very high, and cracks become distinctly larger and more numerous.

This foamy, porous structure facilitates later extraction of components during brewing, but it also means the bean loses density and becomes more brittle.

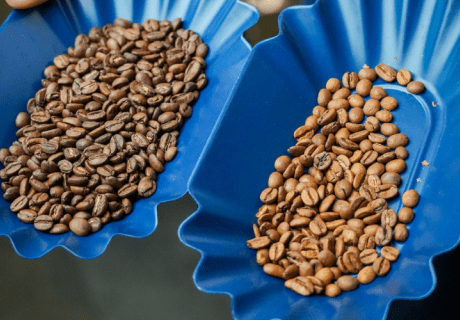

Color Change

The initially greenish bean undergoes color changes during roasting from yellow (drying stage) through light brown (cinnamon), medium brown (medium, city roast), to dark brown or almost black (darkest roasts).

The color change is primarily due to the formation of brown melanoidins in the Maillard reaction and the darkening of caramelization products. After the first crack, beans already have a brown color and are considered light to medium roasted (still preserving some of the original light acidity).

As roasting continues, the color darkens—medium roasted beans are medium brown, medium-dark are dark brown with small traces of oil, and dark roasts (French, Italian) are almost black, often with a sheen of oils on the surface.

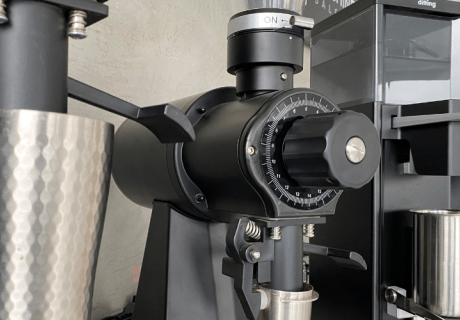

Texture Change and Oil Release

Raw green beans are hard and difficult to grind, whereas roasted beans become increasingly brittle as porosity increases and they dry out. After medium roasting, a bean can be easily crushed between fingers (it's porous like a toasted sponge).

With very dark roasting, coffee oils begin to emerge from the pores of ruptured cells onto the surface. This makes dark-roasted beans shiny and slightly greasy in appearance. These oils contain dissolved aromas—on one hand, they give coffee a full "body" (heavier mouthfeel), but on the other hand, their oxidation after roasting accelerates coffee staling.

Light and medium-roasted beans usually remain matte and dry on the surface (oils remain inside). The texture also changes inside—cell walls become thinner, and the structure becomes more glassy (it goes through the so-called glass transition point during the first crack). This brittleness makes roasted coffee easier to grind and releases its contents during extraction.

Effect of Roasting Parameters on Chemical Composition and Brew Characteristics

Scientists have long studied how different roasting profiles affect the chemical properties of beans and the taste and aroma of coffee brewed from them. In recent years, particular attention has been paid to the effect of roasting temperature, roasting time, and degree of roasting on the content of bioactive substances and the sensory characteristics of the brew.

Roasting Degree as the Main Flavor Factor

Extensive research analyzing coffee sensory properties has shown that the degree of roasting (the "color" of the bean) most significantly affects the flavor profile of the brew, much more than the roasting time itself. Both higher final temperature/darker color and longer roasting time were associated with increased bitterness and decreased acidity, fruitiness, and sweetness in flavor.

In other words, the darker the roasted coffee, the more bitter and full it tastes, with fewer bright, acidic notes. However, an interesting discovery was that with the same degree of roasting, changing the time profile also matters: longer development time after the first crack (called "development time") significantly affected the taste, more than the time to reach the first crack.

Extending the phase after the first crack (without changing the target color) favored the development of more intense aromas (probably due to more complete Maillard reactions), while shortening this phase gave a more "underroasted," acidic profile.

Content of Bioactive Compounds and Roasting Profile

Coffee roasting affects the levels of some health-promoting ingredients, such as polyphenols (e.g., chlorogenic acids) and antioxidant activity. Lighter roasted coffees retain more chlorogenic acids, which are powerful antioxidants but also give the brew acidity and astringency.

As roasting progresses, chlorogenic acids degrade—it's estimated that light roasting loses ~45-54% of these acids, and dark roasting up to ~90%. Interestingly, due to the Maillard reaction, new compounds with antioxidant properties—melanoids—are formed. Therefore, medium-roasted coffee can have the highest antioxidant activity, even higher than green coffee, thanks to the synergy of remaining polyphenols and newly formed melanoidins.

In other words, moderate roasting can increase the antioxidant potential of the brew, despite reducing the content of original antioxidants, because others take their place (although very dark roasting already reduces this activity).

Substances Affecting Health and Safety

The roasting profile also influences the presence of certain undesirable compounds. For example, acrylamide—a potentially harmful compound formed when roasting starch—appears in coffee mainly at the beginning of roasting (especially in the "yellow" phase). The darker the roasted coffee, the less acrylamide, as it decomposes at high temperatures.

Paradoxically, light-roasted coffees have the most acrylamide, and very dark ones the least (although these levels are relatively low compared to other cereal products). On the other hand, compounds such as furans or smoky phenols increase with very intensive roasting, which may slightly lower the health benefits of dark roast coffee.

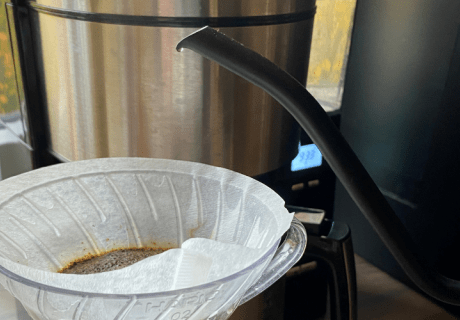

Sensory Characteristics of the Brew and Degree of Roasting

Scientific studies have confirmed the regularities known in the industry: light roasting = brew with greater acidity, fruity/floral aromas, lighter body; dark roasting = more bitter brew, with lower acidity, but heavier, with notes of chocolate, nut, smoke.

Interestingly, in the sensory study mentioned above, it was also noticed that longer roasting time (with the same bean color) increases the sensation of bitterness and "baking" in the taste. This may be due to more "baked" and "roasted" notes resulting from longer heat exposure. Meanwhile, shortening the roasting (reaching a given color faster) leaves more floral-fruity aromas typical of shorter-lasting reactions.

The coffee roasting process is a fascinating blend of science and art. In just a few minutes, an unassuming green bean undergoes intense physical transformations—losing water, swelling to twice its size, cracking with a pop like popcorn, and taking on a dark brown color—and even richer chemical transformations, during which hundreds of compounds decompose and recombine, creating new flavors and aromas.

The Maillard reaction and caramelization give coffee its sweetness, depth, and brown color; amino acid degradation provides fragrant aldehydes and releases CO₂; and the resulting oils and melanoidins build the body of the brew.

Understanding these processes allows coffee roasters to perfect their craft—adapting the roasting profile to a given bean, controlling quality, and consistently extracting desired flavor notes. At the same time, science continues to discover more secrets: how subtle changes in temperature or time affect the chemical composition and health properties of coffee.

.png/460_320_crop.png?ts=1769780365&pn=blog_front)